Singapore Prisons

Historical Overview

Over 30,000 Australians became prisoners of war (POWs). Over two-thirds were taken prisoner by the Japanese at the beginning of 1942. The remaining third were taken prisoner by the Vichy Regime and the Germans.

The treatment of Australian prisoners of war at the hands of the Japanese was brutal. They were often forced to live in uninhabitable jungle, at the mercy of the elements, endure hours of exhausting physical labour, receive no medical treatment, be starved, taunted, abused, maltreated, beaten and derided by their Japanese captors.

The Japanese treatment of prisoners of war was not in accordance with the various international conventions regarding the human rights of prisoners. Instead, it often ended in the deaths of their prisoners. The inhumane treatment of POWs was not forbidden in Japanese culture. In January 1941, the Japanese Minister for the army, General Hideki Tojo issued a 'no surrender' clause in a battle ethics brochure. This clause explained that it was more honourable for Japanese soldiers to die in battle than surrender. Japanese soldiers therefore often had little respect for the human rights of prisoners. They considered surrendering troops morally weak.

Singapore - Changi

The name Changi is synonymous with the suffering of Australian prisoners of the Japanese during the Second World War. This is ironic, since for most of the war in the Pacific, Changi was, in reality, one of the most benign of the Japanese prisoner - of - war camps; its privations were relatively minor compared to those of others, particularly those on the Burma - Thailand railway. For much of its existence Changi was not one camp but rather a collection of up to seven prisoner - of - war (POW) and internee camps, occupying an area of approximately 25 square kilometres. Its name came from the peninsula on which it stood, at the east end of Singapore Island. Prior to the war the Changi Peninsula had been the British Army's principal base area in Singapore. As a result the site boasted an extensive and well-constructed military infrastructure, including three major barracks - Selarang, Roberts and Kitchener - as well as many other smaller camps. Singapore's civilian prison, Changi Gaol, was also on the peninsula. 14,972 Australians were taken prisoner when Singapore surrendered to the Japanese on the 15th. February 1942. There were contrasting experiences in the various prison camps on Singapore.

At Changi, prisoners enjoyed relative autonomy, whereas at Outram Road prisoners were frequently subjected to beatings. Changi was a British peacetime garrison situated on the north - eastern tip of Singapore. It served as the headquarters for prisoners of war on Singapore during Japanese occupation. Most of the Australians captured in Singapore were moved into Changi on the 17th. February 1942. They occupied Selarang Barracks, which remained the AIF Camp at Changi until June 1944. For many, Selarang was just a transit stop as working parties were soon being dispatched to other camps in Singapore and Malaya. Initially prisoners at Changi were free to roam throughout the area but, in early March 1942, fences were constructed around the individual camps and movement between them was restricted.

In August, all officers above the rank of colonel were moved to Formosa (present - day Taiwan), leaving the Australians in Changi under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Frederick "Black Jack" Galleghan. Security was further tightened following the arrival of dedicated Japanese POW staff at the end of August 1942. Nearly 15,000 prisoners were housed in Selarang Barracks, which had been built to accommodate a capacity of 900.

|

|

| Selarang Barracks was home to the 2nd. Gordon Highlanders. | After the fall of Singapore, Selarang Barracks accommodated about 15,000 POWs. |

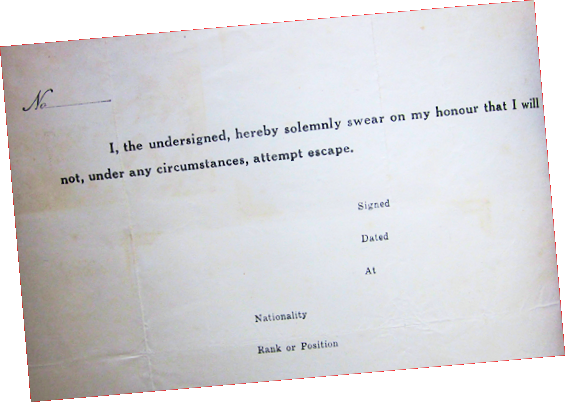

Selarang Barracks Incident

The new Japanese commandant requested that all prisoners sign a statement declaring that they would not attempt escape. The prisoners refused en masse and, on 2nd. September, all 15,015 British and Australian prisoners were confined in the Selarang Barracks area. After three days a compromise was reached: the Japanese ordered the declaration be signed, thus making it clear that the prisoners were acting under duress, and the prisoners were returned to their original areas. Any of the men who did attempt to escape were summarily executed. This confrondation with the Japs was known as "The Barracks Square Incident".

The barrack interiors were overcrowded and hot. The Japanese allowed the soldiers to sleep outside. The Australians made wooden stretchers for more comfort. Unlike other POW camps, the Japanese Administrators of Changi allowed the Commanding Officers of the British and Australians to discipline their soldiers and maintain order. Initially the entire camp came under the control of British Lieutenant General Percival who had been the head of Singaporean defence forces prior to the surrender. A strict regime of discipline and routine was imposed on the soldiers by their own Commanders in order to maintain hygiene, health and morale.

Food stood at the top of the list of priorities for Commanding Officers. Compared with other POW camps, Changi provided prisoners with a relatively varied menu from their daily rations:

| 1.1023 pounds rice (17.6 ounces) | 0.033 pounds milk (.52 ounces) |

| 0.11032 pounds meat (1.76 ounces) | 0.044 pounds sugar (.70 ounces) |

| 0.11032 pounds flour (1.76 ounces) | 0.011 pounds salt, tea, cooking oil (.17 ounces) |

| 0.22 pounds vegetables (3.52 ounces) |

British and Australian army cooks did not know how to cook rice. They often served it as a lumpy grey porridge like mixture. Eventually, cooks improvised and were able to provide prisoners with food that contained basic vitamins, protein, and carbohydrates. In February and March 1942, the Japanese began to clamp down on the healthy appetites of their inmates. They announced that the prisoners should be self-sufficient for all their food except for rice. Immediately, the prisoners made communal vegetable gardens. The Japanese then limited the amount of space which the prisoners could use. Initially, prisoners were free to travel anywhere within Changi, between barracks, into courtyards and surrounding areas. Eventually, the prisoners' attentions turned to entertainment and education. An education program was created which turned Changi Prison into 'Changi University'. Classes on agriculture, business, foreign languages, engineering, law, medicine and science were started. The Japanese allowed the education program to continue but cracked down on the pleasant atmosphere. The school was run until liberation of the prison camp.

Prisoners at Changi were used in work parties. The first party was 750 strong and soon parties reached numbers as high as 8,200. At first, prisoners were eager to work as it freed them from the mundane existence they endured in their cells. Labourers were rewarded with 4 ounces of meat. Their first projects involved levelling bomb shelters, filling shell craters, unloading ships, and stacking food. However, the workload steadily increased as more projects were invented. The Japanese decided to enlarge the aerodrome at Changi. Prisoners were used to construct the aerodrome while officers were transferred to other parts of Singapore for administration. Work on the aerodrome was harrowing - they were forced to work ten to twelve hour days in the sun and humidity. Their food rations were not improved - the 4 ounces of meat soon stopped being distributed.

Industries within Changi

Many everyday commodities were not provided by the Japs so a system of industries developed to supply much needed supplies from articles such as toothbrushes and smoking pipes to medical supplies. (These lists are taken from Bob Kelsey's diary - started in Australia before his deployment and kept hidden from the Japs throughout the war)

| Everyday articles | Medical supplies | |

| 1. | Rubber shoes & clogs | Vit. B extract from Tapioca leaves |

| 2. | Welding (fence wire used for electrode) | Dental rubber dams from latex |

| 3. | Book binding using latex, rags & rice paste | Dental silver from Amalgam |

| 4. | Coconut frond platting | Builders cement & plaster of paris from decomposed granite |

| 5. | Nail factory | Ultra Violet Ray apparatus from bits and pieces in form of carbon arcs |

| 6. | Sawmill & furniture factory | Infra Red Ray using electric iron elements & reflector |

| 7. | Charcoal | Magnesium Carbonate from sea water |

| 8. | Salt from sea water | Iron tonic |

| 9. | Brushes and brooms from bamboo, coir and fibres | Latex for adhesive plaster |

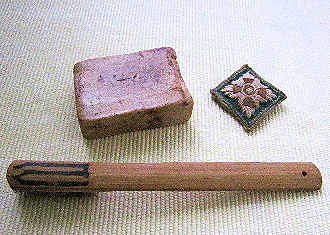

| 10. | Tooth brushes from bamboo, coir and fibres | Kaolin (white clay) into Alkaline mixture |

| 11. | Tobacco from bulk leaf and sugar (called "Grannies Armpit" or "3 Beards") | Asthma treatment from Stramonium leaves |

| 12. | Boot polish from damar (resin) | Grass extract |

| 13. | Smoking pipes from bamboo, clay & guava wood | Yeast from peelings |

| 14. | Chalk and pottery from clay | Medical alcohol from peelings |

| 15. | Dishes from light shades | Rice polishing extract for treating Beri Beri |

| 16. | Hollow ground razors | Soap from oils, ash & salt water |

| 17. | Indoor method of composting | Toothpowder from ashes |

| 18. | Urine 1 - 4 as nitrogenous fertilizer | Paper from grass |

| 19. | Ink from carbon paper, lead pencils & type writer ribbons | Artificial limbs from bits and pieces & Jap aluminium from crashed planes |

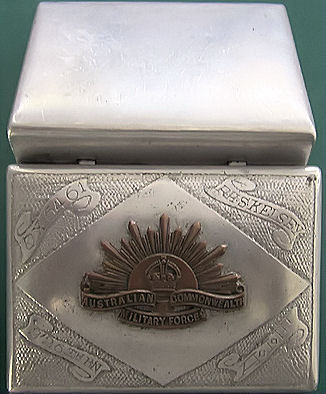

| 20. | Aluminium articles from fan blades & crashed planes | Iodine from sea water and seaweed |

| 21. | Coir rope from coconut fibres | Prussic acid from tapioca |

| 22. | Dartboards and darts (made from brass pins punched out of hinges | Crutches |

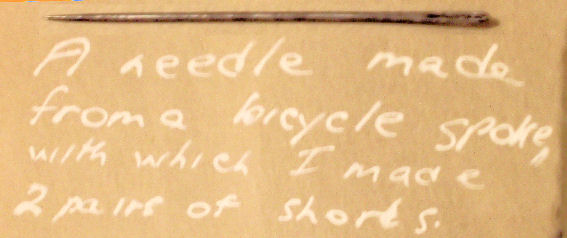

| 23. | Darning needles from bicycle spokes | Amalgam from thermometer mercury |

| 24. | Cotton from unraveled string and socks | |

| 25. | Latex patching on clothes and shoes | |

| 26. | Dixies, billys and buckets from soldiers boxes and empty tins | |

|

|

|

| This remarkable and quite beautiful cigarette case was made from aluminium stolen from a Jap aircraft, complemented by a "Rising Sun" badge and hand engraved with "QX6461, RHS Kelsey, 2/26th Bn and A.I.F" | A piece of soap, a toothbrush made from bamboo & coir and an officers "pip" made by unravelling canvas or cloth, dying it and then sewing the badge with a needle made from a bicycle spoke. | |

|

Making a needle from a bicycle spoke seems trivial however in Changi it was quite an achievement and Bob was proud of his needle and the use to which he put it - making and repairing his clothes, his "Pips", book binding and repairing his diary, making thongs. | |

The prisoners suffered from performing manual labour. Lack of vitamins provided by food saw the development of skin sores, ulcers and other medical conditions. Diarrhoea and dysentery broke out as it was difficult to maintain hygiene. Other tropical diseases also plagued the prisoners. In March 1945, as Japan faced defeat in the war, food rations were cut. Prisoners received only 8 ounces of rice and 4 to 6 ounces of vegetables. The vegetable gardens the prisoners had nurtured were important dietary supplements, saving them from starvation. Throughout the war the prisoners in Changi remained largely responsible for their own daily administration. The main contact with the Japanese was at senior officer level or on work parties outside the camps. Extensive gardens were established, concert parties mounted regular productions, and a reasonably well equipped camp hospital operated in Roberts Barracks. Damaged infrastructure was progressively restored and both running water and electric lighting were common throughout the Changi area by the middle of 1943. Camp rations and supplies were supplemented by the opportunities that work parties provided for both theft and trade. However, most prisoner activities suffered after May 1942 when large work parties began to be sent out of Changi to work on projects such as the Burma - Thailand railway. In February 1942 there were around 15,000 Australians in Changi; by mid 1943 less than 2,500 remained.

In May 1944 all the Allied prisoners in Changi, now including 5,000 Australians, were concentrated in the immediate environs of Changi Gaol, which up until this time had been used to detain civilian internees. In this area 11,700 prisoners were crammed into less than a quarter of a square kilometre: this period established Changi's place in popular memory. Rations were cut, camp life was increasingly restricted and in July the authority of Allied senior officers over their troops was revoked. Changi was liberated by troops of the 5th Indian Division on 5th. September 1945 and within a week troops were being repatriated. The main body of the 2/26th, 470 men, returned to Australia aboard the ship Largs Bay, berthing at Pinkenba Wharf in Brisbane on 7th. October 1945 and disembarking the next day for a parade through Brisbane.